|

|

| |

Generation 1

|

Mid-18th Century

Pre-contact SíKlallam Indians inhabited the northern shores of the Olympic Peninsula along the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Hood Canal. The village of Chief Ste-tee-thlum was located between the mouth of the Dungeness River and what later became Jamestown, land owned by SíKlallam families. The marriage of Chief Ste-tee-thlum the Younger with Tísus-khee-na-kheen, the Princess of Nanaimo, followed a long-standing practice of marrying royalty from a neighboring tribe. Although she was kidnapped it did eventually cement an alliance between the two tribes. Status and honor also accompanied choosing a bride from Vancouver Island.

|

Generation 2

|

Late 18th to 19th Century

The traditional life style of the SíKlallams continued into the 19th century partly because of their geographic isolation but also because the early white explorers came and went and therefore had little impact on them. The SíKlallams reputation as fierce warriors, expert hunters in the forests and superb fishermen and canoeists on the water stood them in good stead with neighboring tribes. Six sons and one daughter were born to Chief Ste-tee-thlum and his Nanaimo wife with Eíow-itsa, the little sister being the youngest. When the ship Gadboro arrived and fired on the local Indian villages this included the village of Ste-tee-thlum. The panicked SíKlallams fled and Eíow-itsa, a three week old baby, was accidentally left hanging in her cradle in the family longhouse. She was later rescued, unharmed, and the all-but-destroyed village was moved to a more protected and less exposed location. At age 14 (1806) Eíow-itsa married. A factor of the Hudson Bay Company called her Julie Ann and her husband became known as John Jacob. It is around this period in the early 19th century that SíKlallams also acquired English names.

|

Generation 3

|

19th Century

In the 19th century the effects of earlier smallpox epidemics and the significant numbers of white settlers arriving on the Olympic Peninsula changed life forever for the SíKlallams. Specifically, The Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850 and The Point-No-Point Treaty of 1855 had devastating effects on their traditional way of life and this included the inability to hold onto their lands. Indian agents and Christian missionaries also exacerbated their traditional life styles. The two sons of Eíow-itsa, Soo-yahitch (Henry Jacob) and Chumahan (Jacob Jacob) lived in this era with Soo-yahitch being one of the signers of The Point-No-Point Treaty.

|

Generation 4

|

Mid-19th to Mid-20th Century

Many changes took place on the Olympic Peninsula during the latter half of the 19th century. The white settlers dominated the area and illegally took possession of SíKlallam tribal lands and tried to force them onto small reservations. Many SíKlallams resisted and refused to leave. In 1874 a group of SíKlallams bought land near Dungeness and began the Jamestown community. In the House of Ste-tee-thlum, Chumahan and his wife had two daughters, both of whom became gravely ill with smallpox at ages seven and six. Only one survived, Himoyitsa or Annie Jacob. Her life spanned almost half of the 19th and half of the 20th century. She married Charles Lambert, an immigrant from Sweden, and after his death Bartolo Reyes, a ship-wrecked sailor from Chile. She had eleven children.

|

Generation 5

|

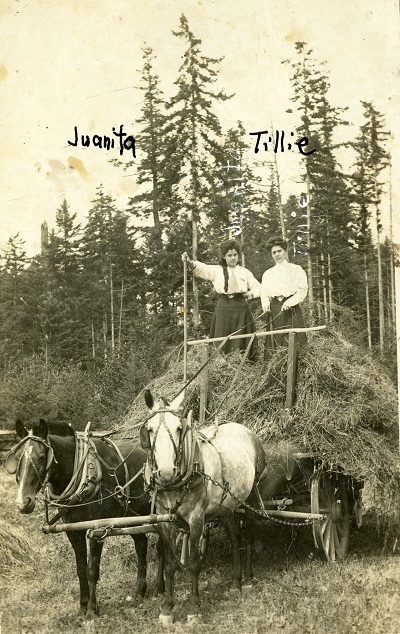

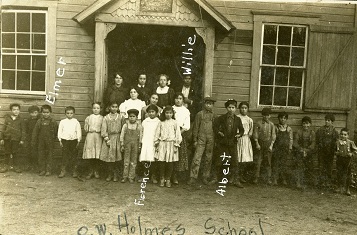

1870s to 1970s

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries SíKlallams basically learned to adapt their way of life to be compatible with the non-Indian world. Most became known by their English names. In the field of education Jamestown had its own schoolhouse as early as 1878 whereas children living in Blyn could attend the Oliver Wendell Holmes School after it opened in 1892. In 1910 Sequim built its first school. Every child of Annie Jacob Reyes attended school in Blyn where the family had its farm. Her eighth child Florence went on to receive a high school and college education and became a teacher.

|

Generation 6

|

1920s to Early 21st Century

By the mid 20th century SíKlallam/Indian assimilation into white society had largely taken place. This did not mean, however, that persecution, racism and ignorance about Indians and their culture did not occur. With a backdrop of the Great Depression, World War II, Sputnik and the Cold War, the children of Florence Reyes MacGregor: Betty, Andy and Juanita, put great emphasis on family, feasting and gift-giving, all vital elements of their traditional SíKlallam inheritance.

|

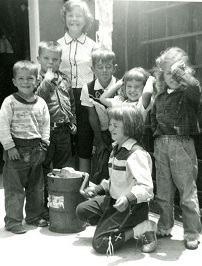

Generation 7

|

1940s to Present

The second half of the 20th century in the U. S. was characterized by the popularity of television, the social upheaval of the 1960s, the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, the Feminist Movement, the American Indian Movement and a general disillusionment with the establishment and government. However, maintaining their Jamestown and Indian identity gave SíKlallams a firm foothold and they laid stress on the importance of family and community. This sense of community was further strengthened in 1981 with Federal Recognition of the Jamestown SíKlallam Tribe. One of the many people to work on this long and laborious process for recognition was Judge James Bowen of the Reyes MacGregor family.

|

Generation 8

|

1960s to Present

The technology boom of the late 20th century has meant that SíKlallams along with everyone else now live in a global society. Vast numbers of home electronics, especially computers and cell phones, became affordable and were heartily embraced by the young. Raised in homes where either both parents worked or were divorced this generation was nevertheless encouraged to be themselves without racial or gender role expectations. In the Reyes MacGregor family this generation is now making contributions in the fields of education, engineering, communications, accounting, music, law and the veterinary sciences.

|

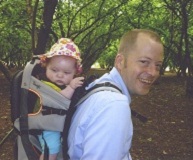

Generation 9

|

1990s to Present

Still quite young this generation has inherited a global world in an age of technology. Their parents and grandparents are giving much thought to the development of these childrenís minds and life experiences. Yet as descendants of the House of Ste-tee-thlum these children are distinctly aware of their rich native heritage and culture. They too are part of the future of the SíKlallams, ďThe Strong PeopleĒ.

|

|